We live in a “prove it” culture, dating back several centuries. Once upon a time the supernatural was recognized as just as real as the natural, and spiritual forces were just as valid as physical ones. In much of the world this still holds true today, but not in the West. Enlightenment thinking brought with it a mind-set that man is central, the highest life-form. The fallout of that is that god (not God) is whatever people want him or it to be. And for many, it means that God does not exist. They see the lack of empirical evidence for God to be proof that He does not exist.

The argument against God’s existence is the most extreme response to mystery. Because the biggest questions of why and how cannot be answered clearly, the assumption is that no God exists to answer them. The world has evolved to where it is, there is little purpose to our being, and when life ends it ends completely. Many atheists came to that point of view through pain and suffering. They saw no rhyme or reason for it and could not reconcile it with a good and loving God, so their conclusion was that God simply could not exist.

Faith is the great cop-out, the great excuse to evade the need to think and evaluate evidence. Faith is belief in spite of, even perhaps because of, the lack of evidence.

—Richard Dawkins

This response to the mystery of why leaves the asker no more satisfied than if there were a God he or she simply couldn’t understand. It plainly says that mystery exists because mystery exists—in this case the mystery of pain and suffering. Atheists find it satisfactory, at least to a degree, to have “eliminated” one source of mystery because it doesn’t fit their framework of the world. By their definition of “good” and in their understanding of “powerful,” a God who allows for or brings about pain cannot be a good God. Therefore He cannot exist. The end.

Such a framework that God has to fit in to will inherently limit Him. It demands that He make sense to us, and if He doesn’t, it is He who must change, not us. Most people don’t outright eliminate God; they simply diminish Him. Some view Him as lacking power—God is not omnipotent. Some view Him as distant—He kick-started the world and now lets it run on its own. This is a belief similar to Deism. While most Christians would not espouse it, for many, their lives indicate they are functional Deists. They believe in the existence of God but not His power or participation in daily life. In fact, most of us fall into this.

Forgetting God

In the movie The Usual Suspects, Kevin Spacey’s character, “Verbal” Kint, says one of the great lines in recent movie history: “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” While this is true, equally as true is the ease with which we forget God exists. We go through life as lords of our own little universes, solving problems with our own abilities and strengths and depending on external circumstances or therapies to massage our moods. We forget God until we are at wit’s end, then we cry out for help. We don’t need Him at work. We don’t need Him at school. We don’t need Him anywhere. Until we do. Then we seek to summon Him from on high or wherever it is that He waits until we beckon. We live most days as if we appreciate God’s good work in making the world and are glad He went home when He was finished, kind of like the contractor who built the addition on your house.

When we aren’t forgetting God, we’re often trying to release Him from responsibility for things we don’t understand by diminishing His knowledge of events or ability to impose Himself on the choices of people. Some theologians have questioned God’s foreknowledge, His ability to know what will happen in the future; because if He has that, it must mean He has determined the future, which would take away human free will. On a more personal level we often emphasize the evil of a person or the randomness of nature when tragedy strikes, and we ignore, intentionally or otherwise, the fact that God is omnipotent and that He Himself says, “I make well-being and create calamity.”

Of course none of our frameworks for God have any actual bearing on who He is. Each simply represents a framework, a box, into which people fit God to make themselves feel better about who He is.

Ultimately, these frameworks stem from hearts that cannot abide submitting to someone else as all-powerful. To do so would mean relinquishing control of their own lives and, just as difficult, their understanding of the world. If I believe that I am the most important being in the world, I will create a system into which the world fits and that suits my sensibilities. As a finite person, I will shrink the world to fit my finitude. And that most definitely excludes an infinite God.

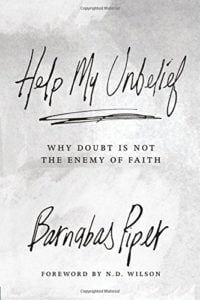

This is an excerpt from my book, Help My Unbelief: Why Doubt is Not the Enemy of Faith.